I don’t want to shock anyone, but in the United States, Americans used to be allowed to own other people. Not in a bad employment contract kind of way—where your boss takes up all your time and underpays you—but in a literal I-own-your-body-and-can-do-whatever-I-want-with-it, including forcing you to have children that I can then sell to someone in another state kind of way. And just in case that wasn’t horrifying enough, this system—what we now politely call a peculiar institution—was legally reserved for people who had been kidnapped from Africa and shipped across the Atlantic in inhumane conditions, along with their descendants.

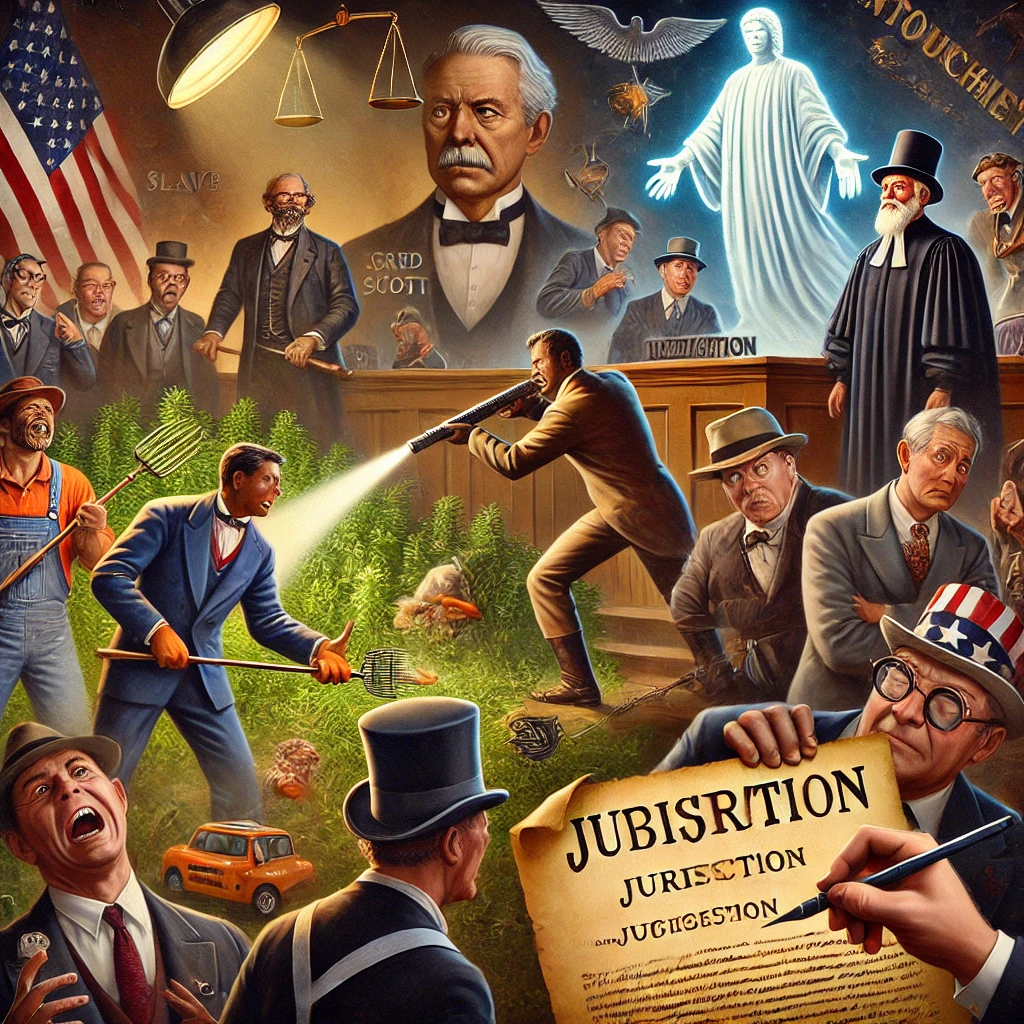

If that wasn’t bad enough, the Supreme Court decided in Dred Scott v. Sandford that not only did enslaved people not automatically gain freedom by being taken to a free state, but that they—and by extension, any Black person—could never be American citizens. No standing in court. No rights. No recognition of their personhood.

Eventually, slavery was abolished—first in a limited way through the Emancipation Proclamation and then officially with the 13th Amendment. But there was still a problem: Dred Scott was still on the books. The legal system still provided cover for people who wanted to keep treating Black Americans as second-class citizens. Fixing that required more than a new law or executive order—it required a constitutional amendment. Enter the 14th Amendment.

The very first thing the 14th Amendment does (in Section 1) is define who gets to be a citizen of the United States. The Constitution had already given Congress the power to set naturalization rules for immigrants, but that didn’t cover people born here. So, the amendment made it simple:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside.

That’s it. That’s the rule. No wiggle room. If you’re born here, you’re a citizen—unless you’re not subject to U.S. jurisdiction. This was meant to ensure that the children of formerly enslaved people—who had no official citizenship status—would be protected. But it was also written carefully to exclude the children of diplomats, who, thanks to diplomatic immunity, are subject only to the laws of their home country.

Now, I suppose you could argue that the framers of the amendment didn’t want to automatically grant citizenship to Indigenous people either. The legal status of Indigenous nations has always been complicated, and while that’s an interesting conversation, it’s not actually relevant here. What is relevant is the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof.”

Let’s pause for a quick analogy.

If you were alive in the late ’70s or early ’80s, you might remember The Dukes of Hazzard. Bo and Luke Duke were constantly running from the corrupt county sheriff, Roscoe P. Coltrane, who wasn’t really working for the people so much as serving Boss Hogg. A lot of their escapes involved making it to the county line because back then—and still, to some extent today—a sheriff’s jurisdiction only extended to their own county. Roscoe couldn’t arrest people across the line or enforce laws outside his authority. That’s what jurisdiction means.

So when the 14th Amendment says that birthright citizenship applies to people “subject to the jurisdiction” of the U.S., that means anyone subject to U.S. law. If you are born here and can be arrested, tried, and convicted under U.S. law, then congratulations—you qualify as being under U.S. jurisdiction.

Now, here’s where things get interesting. Some politicians today are trying to argue that the children of immigrants aren’t actually U.S. citizens. But if that were true, then by necessity, those children wouldn’t be subject to U.S. jurisdiction. And that would mean that their parents—immigrants—also aren’t subject to U.S. jurisdiction, which would, logically, grant every immigrant in the country the equivalent of diplomatic immunity.

At which point, congratulations to every undocumented worker in America—you’re officially a spy. Welcome to The Untouchables: Birthright Edition, where every landscaper and Uber driver just became a high-level operative, immune to U.S. law and beyond the reach of mere mortals.

And here’s the thing—this is not me making a weird leap in logic. This is their argument, just taken to its natural, absurd conclusion. The people crafting these policies are just grasping at any possible loophole to justify their xenophobia. But they either lack the critical thinking skills—or just don’t care enough—to follow their own logic to its inevitable, ridiculous conclusion. And that’s just one example of the kind of damage this kind of thinking does.

And that’s before we get to the broader implications of tossing out constitutional principles just because they’re inconvenient.

We are in a dangerous time for a lot of reasons.