(A response to Robert Reich’s “Attack on the American Mind”)

Once, in a land once vibrant with stories and songs, there stood a vast and noisy kingdom known as the United Realms of Ehhmerikkah.

It was a peculiar place — part circus, part graveyard, part shopping mall. Its buildings leaned like confused drunks, its citizens wandered in dreamlike scroll-loops, and its rulers were chosen based on how loudly they could shout over fireworks.

But once, long ago, the kingdom had been a place of thought. It had temples filled with scrolls (they called them libraries), towers of curiosity (universities), houses of meaning (museums), and sanctuaries where children learned how to ask “why?” instead of just “how much?”

That was before the era of The Hollowing.

It began slowly, as these things do. A ruler arrived with hair like fried straw and a voice like collapsing drywall. He was beloved by many, mostly because he told them the things they wanted to believe were true — especially the things that weren’t.

He did not like questions. He preferred chants.

He did not like facts. He preferred feelings in costume.

He especially hated Books, which he said were full of “Too Many Words and Not Enough Winning.”

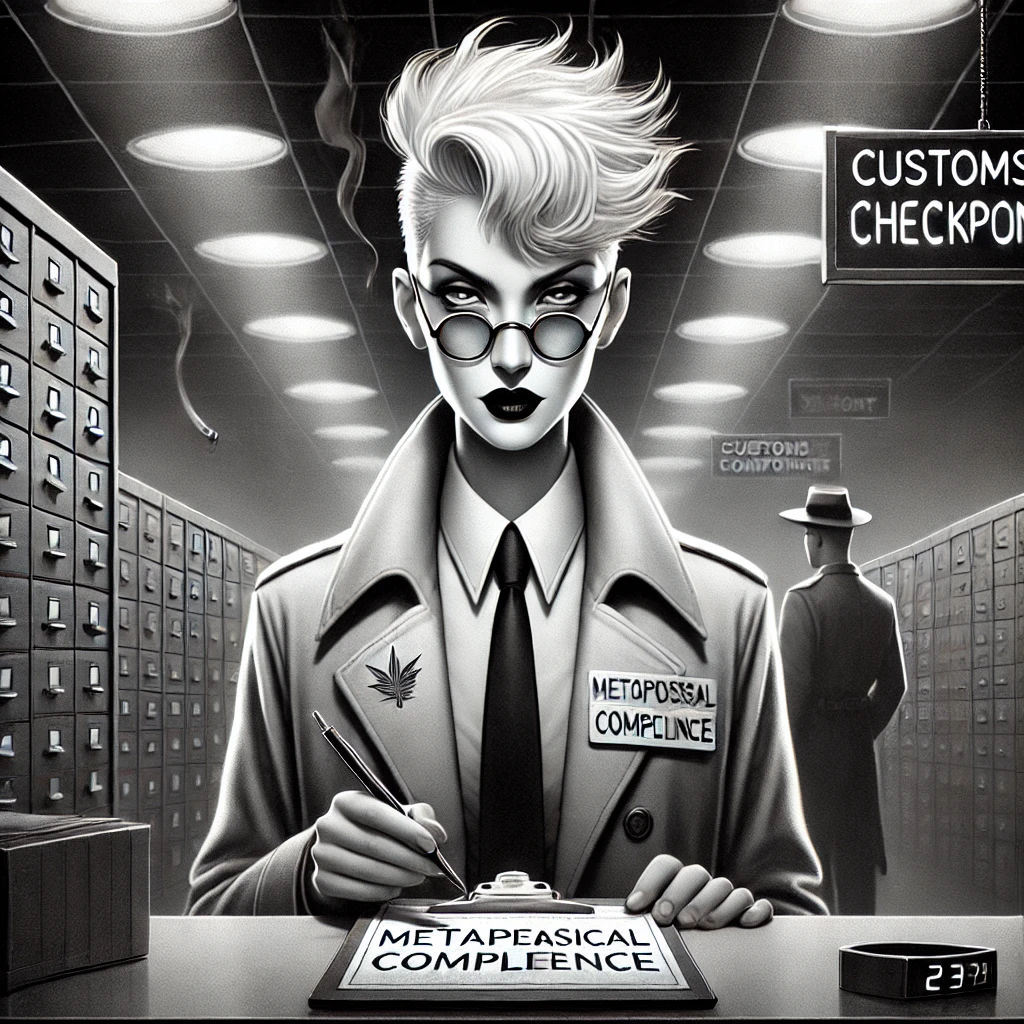

And so, he summoned the Wrestling Priestess, Linda of McMahon, and bade her dismantle the Temple of Learning. “Leave the money bits,” he snarled. “The debt and the tests. But remove the thinking. Thinking makes people squint at me.”

Soon after, the Ministry of Healing lost its scrolls. The Sciences were evicted and replaced with oracles who spoke only in emojis. The libraries, once safe harbors for quiet wonder, were repurposed into Ministry of Patriotism Outlets™ — filled with coloring books and surveillance drones shaped like eagles.

Even the House of Dancing Words, once known as The Arts, fell under siege. Its stewards were replaced with men in crisp suits who’d never danced but insisted they “understood the rhythm of commerce.”

And the people?

Well, many did not notice. Or they noticed but were too tired. Or they laughed and said, “This is fine. Thinking’s overrated anyway.”

But somewhere, beneath a ruined amphitheater, a strange fruit stirred.

It was a Golden Apple, marked in glowing runes: Καλλίστῃ — To the Fairest.

And beside it sat a shriveled, sour lemon, gray as a politician’s smile. It bore a plaque: The Dull Lemon of Absurdity. Not for human consumption.

From the apple came a whisper — not loud, but impossible to ignore:

“When tyrants burn books, we write stories in smoke.

When they silence thought, we build libraries of laughter.

When they blind the eyes of a nation, we become Tricksters, Fool-Scribes, and Saints of Nonsense.

Because while ignorance can rule for a while…

A well-placed joke can crack a crown.”

And from the shadows emerged strange folk — the Abiscorids.

Wielding humor like swords and irony like lanterns, they did not march. They skipped.

They did not chant. They heckled.

They did not kneel before the Hollow Kings.

They offered them rubber chickens and banana peels instead.

They gathered the remnants of the old world — the banned books, the forgotten questions, the censored paintings — and rebuilt a cathedral of nonsense atop a junk heap. They called it:

The Cult of Brighter Days.

And in time, the people remembered how to laugh again — not the numbed laughter of passive screens, but the belly-deep roar of truth told in absurdity.

Because the rulers feared ideas.

But they feared joyful, defiant thinking most of all.

And thus, the American mind — buried but not dead — began to dream once more.